Titled ‘The Warp, The Weft, The Wake’, my 20/20 proposal built on existing research within my practice around the afterlives of slavery, as articulated by cultural theorist Christina Sharpe in her framing of the “wake” – life lived in the aftermath of slavery as grief; as state of watchfulness; as aftermath. It also took as a starting point words spoken by African-American abolitionist Sarah Parker Remond, who visited Manchester & spoke at The Athenaeum – which now forms part of Manchester Art Gallery’s footprint – as part of a tour of Britain in 1859. In a manifestation of Sharpe’s “wake”, Remond’s words reverberate into the present: “not one cent of the money ever reached the hands of the labourers” – still rings true; raising questions around reparations, and continued practices of exploitative labour within structures of capitalist production.

I wanted to take these provocations as a starting point for considering legacies of expansionism, colonialism and exploitative labour inherent to the material history of cotton; thinking about this in dialogue with Manchester Art Gallery’s costume & textiles collection, which resides at their partner gallery Platt Hall. I was interested in how some of these objects in the collection connect to the cotton industry that fuelled the growth of the city, which in many ways funded the institution. I wanted to think carefully about histories of site, channelling some of the strategies of institutional critique in speaking back to these histories of place; with reference to The Athenaeum as speakers’ hall, The Royal Manchester Institution – the gallery’s institutional fore-runner – funded by city’s elite, merchants, and industry owners, and Platt Hall built by a textile merchant and now housing the gallery’s textile and costume collections.

Pattern book at Platt Hall, Manchester Art Gallery Collection. Image: Holly Graham.

Over the course of monthly visits to Manchester between July – October 2023, I was able to view a wide range of the material in Manchester Art Gallery’s collection; across the main gallery, storage holdings at Queens House, and museum of dress Platt Hall. I found a real breadth of possible entry-points, both directly connected, and adjacent to, my original research proposal. However, I was most drawn to a collection of un-accessioned pattern books on the peripheries of the gallery’s collection, alongside patchworks, and the dress collection. I felt these objects held space for intersecting lines of enquiry, drawing together my interest in the discipline of print, intimate and haptic relationships to cloth, and material memory pertaining to labour and cultural influence, and appropriation.

Looking at patchworks from the Mary Greg collection during ‘Textiles & Tall Tales’, a workshop lead by Holly Graham at Platt Hall in March 2024. Image: Holly Graham.

My research also took me beyond the Manchester Art Gallery collection, with local research trips to view RMI subscribers’ records at Manchester Central Library & Local History Archive; an exhibition titled ‘Founders and Funders’ at John Rylands Library looking at connections between University of Manchester’s founders and finances garnered from transatlantic slavery; textile industry photographs & pattern books at The Science & Industry Museum Archive; pattern books and cotton samples at The Whitworth Archive; and the British Textile Biennale & a corresponding conference at Manchester School of Art.

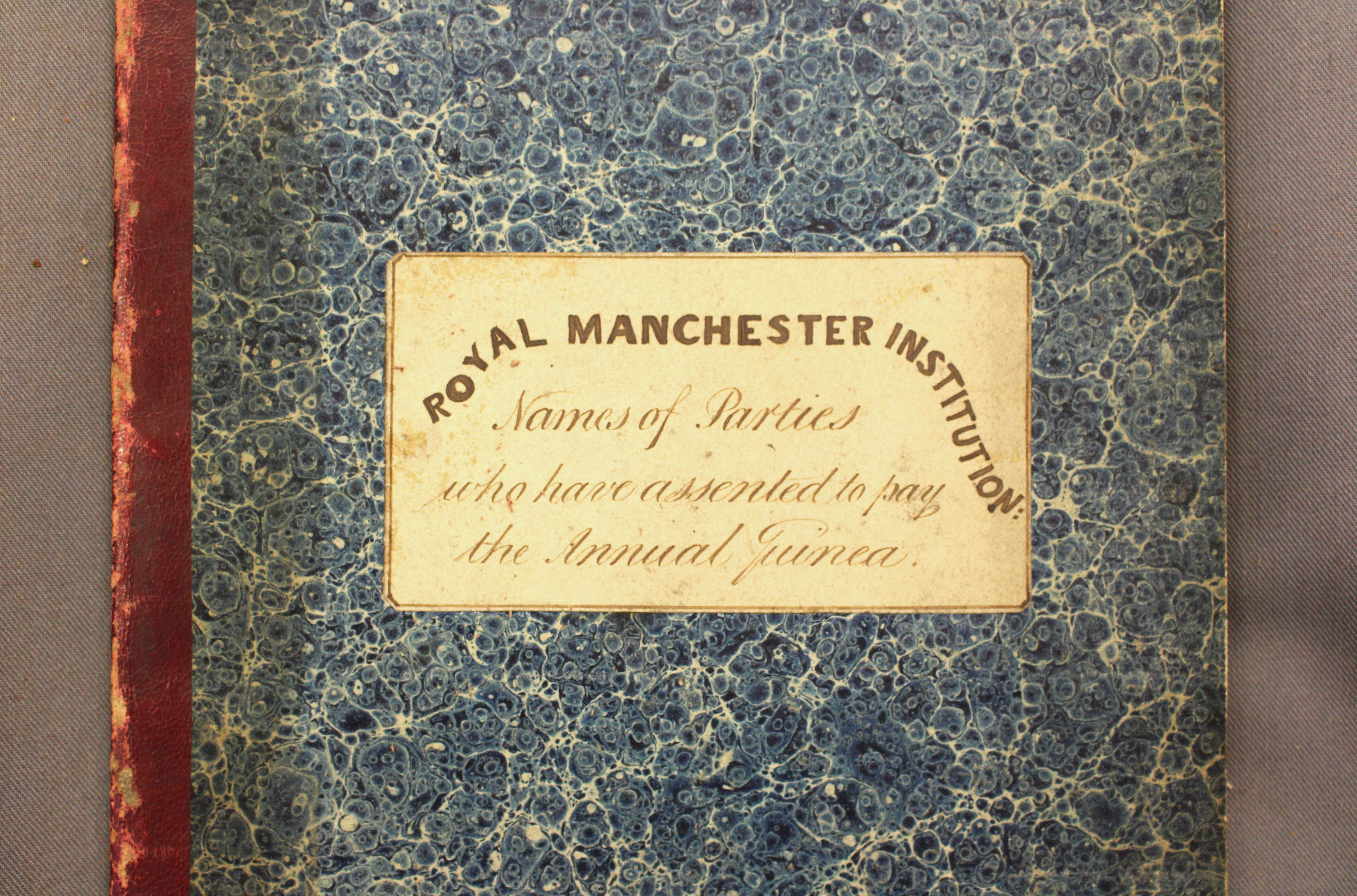

‘Royal Manchester Institution: Names of Parties who have Assented to Pay the Annual Guinea’, 1826-55. Manchester Central Library & Archive. Image: Holly Graham.

During my R&D period I was able to draw on a wealth of knowledge from museum staff, through cross-departmental conversations with a range of curators based across MAG & Platt Hall, as well as community engagement team-members across both sites. This led to us hosting some craft & oral history workshops with local people involved in Platt Hall’s programming, and from local community organisation 422 Arts earlier this year. Though these sessions, I hoped to bring in a range of voices to think about the material from an everyday personal perspective and collectively explore histories of the material, while also thinking about these narratives in relation to how they might be experienced in the gallery. Audio recordings from these sessions has fed into the development of the artwork.

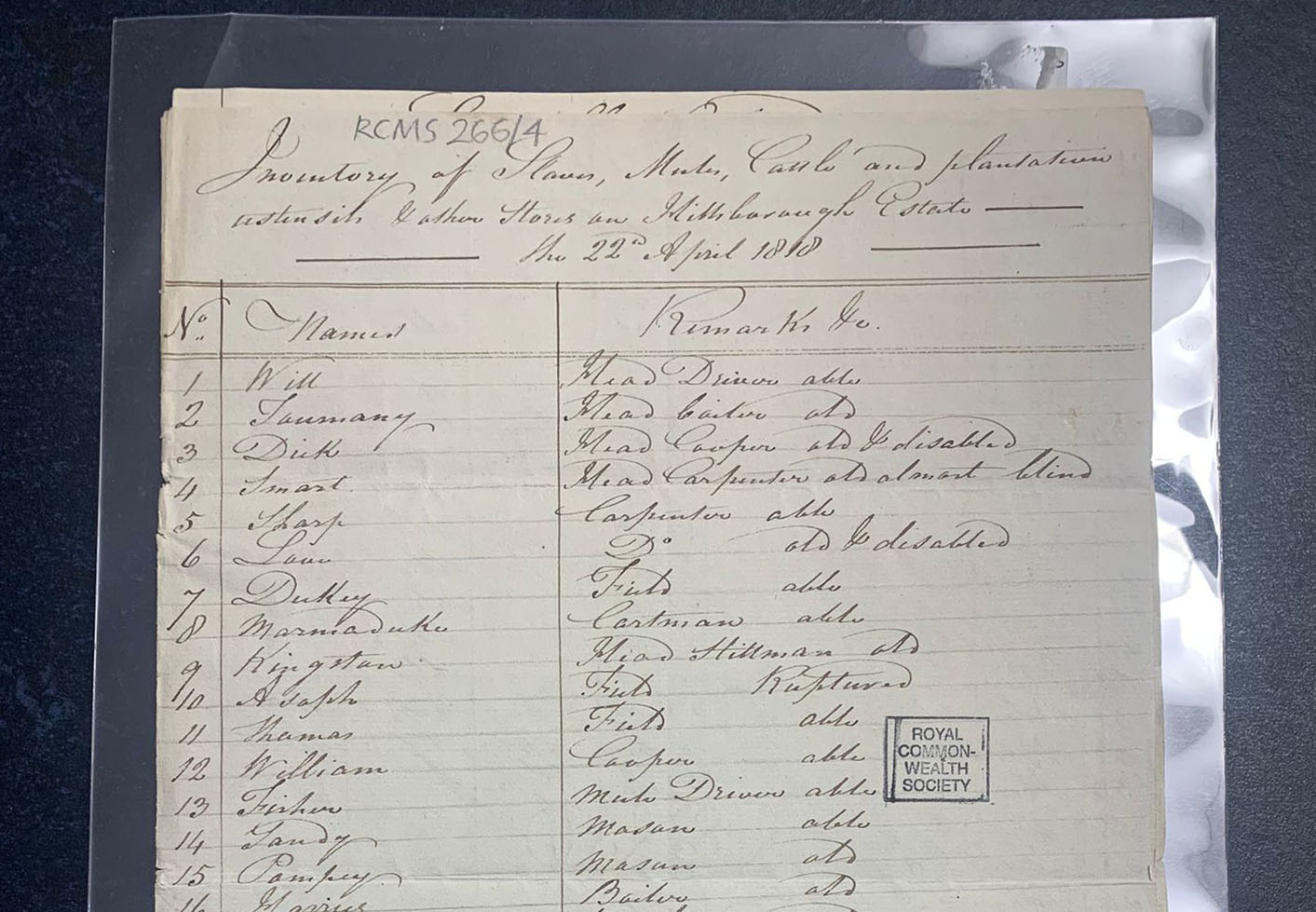

I also worked with Manchester-based initiative Global Threads – a collaboration between UCL and the Science & Industry Museum. Here, I worked closely with Matthew Stallard, with input from Katie Belshaw, to recruit and support three early-career researchers to undertake three areas of study, linked to the two institutions that are key to the establishment of MAG as we know it today. Ella Sinclair used newspaper databased to research activities taking place in The Athenaeum in the same year that Remond delivered her speech; exploring the wider context this abolitionist discourse was entering into. Destinie Reynolds and Serena Robinson took names of individuals who were either founding subscribers of the Royal Manchester Institution, or on the first board of the Athenaeum, as starting points for identifying connections between some of these names and exploitative and enslaved labour. Destinie looked at the experience of enslaved and former-enslaved people on South Carolina’s Edisto Island, a key producer of Sea Island cotton and a noted area supplying Manchester textile manufactory McConnell & Kennedy, business of William McConnell who is noted on the Athenaeum’s first Board. Serena made a trip to Cambridge to view the records of Hillsborough Estate, in Dominica; a plantation owned by the Greg family, who also ran the renowned Quarry Bank Mill in Styal just south of Manchester, and who were significant donors to Manchester Art Gallery’s collection. Some of the cotton produced on the mill would have been sent abroad to clothe enslaved labourers, who in turn worked to generate further profits for the plantations’ owners. All three researchers have written up blog posts, which can be accessed through the Global Threads website.

Central to this research was the desire to identify archival information that spoke of the lives of enslaved people, whose labour ultimately in part financed the establishment of many Manchester Art Gallery, through the wealth generated for and gifted by early subscribers. It aimed to name some of those who’s contributions go largely unrecognised in the RMI ledgers. More can also be said about the experience of local industrial labourers, and the harsh conditions for workers during this period of accelerated capital growth and cotton boom. Their names are also notably absent from these documents.

In response to this research, I’ve been working towards a number of outcomes, which ultimately will take the form of a costume and a museum tour-style work – through audio & possibly performance. In developing the work, I found it helpful to return to key concerns within my practice around materials and how they hold memory and tell stories, and to think about how these histories reverberate into the present. Ideas around craft and design, text and citation, duplication and acceleration, have also remained important considerations for me.

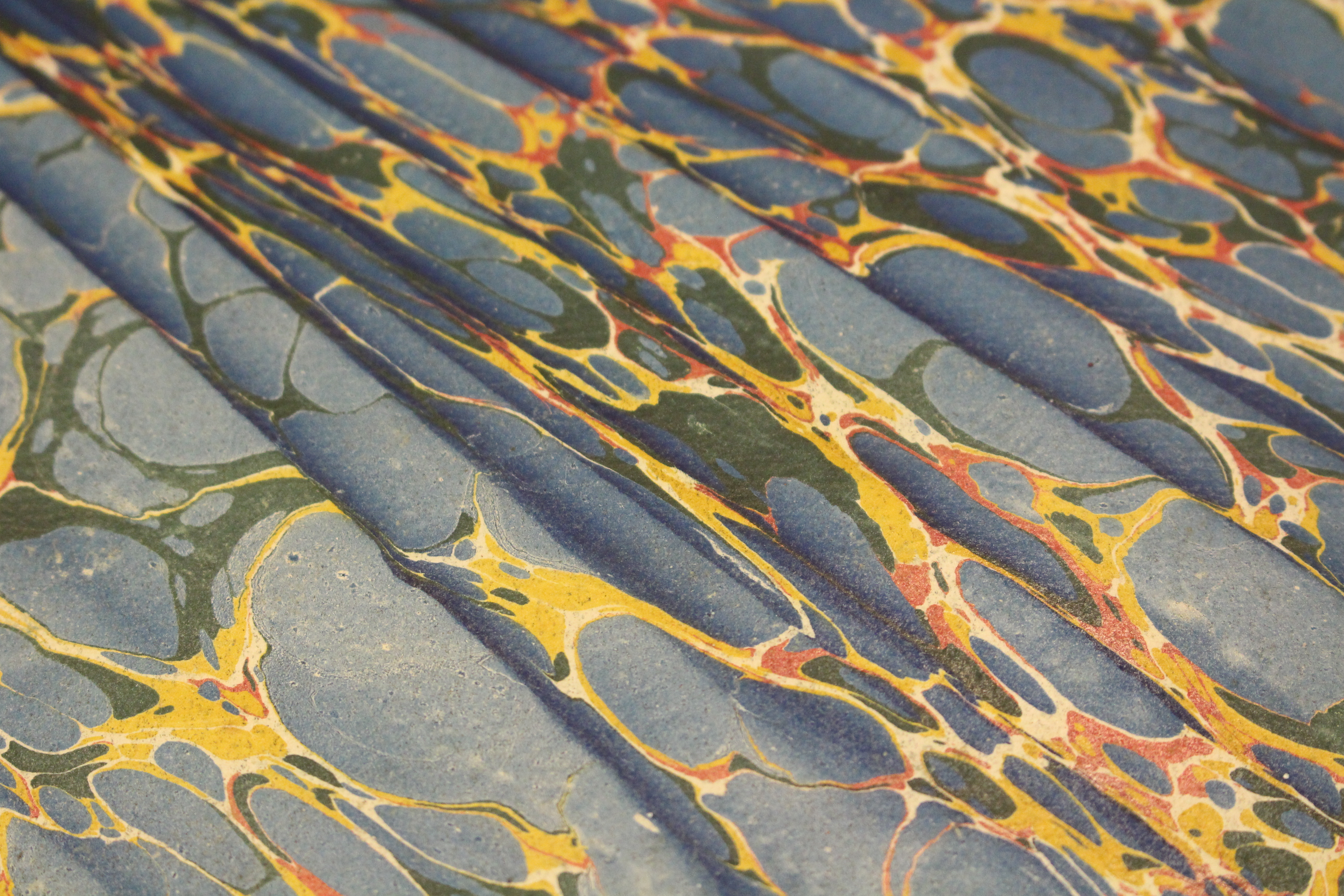

The silhouette of the costume I have been developing is based on a dress worn by Sarah Parker Remond. There are three print designs for the fabric, and these are lifted from a combination of sources. One of these is a rare surviving example of woven Manchester check, also known as ‘Guinea cloth’ – cheaply produced cloth often for sale to West African markets in exchange for goods, including enslaved people. Stumbling across these unassuming woven samples, hiding in plain sight among a run of print swatches, felt like an important discovery; and threw up questions around cataloguing and accessioning: how can we know where these things are kept / how do we make them available for reference? I was also interested in the resemblance of the check print to the grid that bound the names of the RMI subscribers in the institution’s ledgers, and to other lists of itemised names, and records. I liked the idea of the costume taking on the expanded form of one of these books, with the other selected prints lifted from end papers from these same ledgers – of using this format not only to highlight the names of those whose money was assigned to the founding of the institution, but also to signpost towards the names that are not included; and to think about whose labour facilitates the wealth that was then invested into the institution.

Close-up of end-paper in ‘Royal Manchester Institution: Share Registers’, 1823. Manchester Central Library & Archive. Image courtesy of the artist.

Alongside this, the project has offered an opportunity for me to reflect on the possibility of sharing skills cross-generationally, with the potential to collaborate and learn from my mother, Jennifer Graham, who has a career background as a costumier. Over the past month, she has joined me in my studio and has been working to fabricate the dress. Although it is based on my initial dress design, the development of it has been collaborative; with my mum suggesting a range of undergarments, and consulting on historical accuracy, strength and robustness of materials, practical considerations for wearing the costume. We are in constant dialogue about approaches towards embodying the concept and bringing the design to life. And I have been documenting the process, through photographs and video; which offers another potential project outcome.

‘Marble’, ‘Check’ and ‘Stone’ test print swatches. Image: Holly Graham.

The combination of research residency and commissioning opportunity has felt incredibly generative, and has led to the development of a number of different artwork outcomes. The next step will be a process of deciding in dialogue with Manchester Art Gallery, what to select for acquisition into the collection. This will be my first experience of navigating acquisition of work into a national collection, and I imagine it will be a useful learning opportunity. I’ve been grateful to the UAL team for their support and guidance throughout the project, to the MAG and Platt teams for their welcome and generosity in facilitating my research, and to all of the other wonderful individuals mentioned throughout this text who I’ve been privileged to collaborate with.

Jennifer Graham working on construction of the crinoline in Holly’s studio. Image: Holly Graham.

Further Reading from Global Threads:

Edisto Island & McConnell & Kennedy: The invisibilised labour behind Manchester’s mills, by Destinie Reynolds

Culture, Cotton, and Wealth: The Manchester Athenaeum in 1859, by Ella Sinclair

Hillsborough & Manchester: Tracing profits and recovering lives in the archive, by Serena Robinson

Partner Reflection

Manchester Art Gallery

Fiona Corridan, Senior Curator

Rosie Gnatiuk, Costume Curator

Kate Jesson, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art

Reflections by Fiona Corridan, Senior Curator

Holly Graham began working with my predecessor Natasha Howes, so I was late to the project, but luckily a number of colleagues have been working with Holly across our curatorial and learning teams. Two of them have provided their reflections on the development of our relationship with Holly and the collaborative process of researching areas of our collection, working with communities and planning our next steps. The research that Holly has undertaken is vital to our understanding of the history of our institution, specific areas of our collections, and how we present, interpret and talk about them, as well as how we work with people outside the organisation. In addition to acquiring the artwork produced by Holly, we are collaborating with her on a display in March 2025 to contextualise her finished artwork alongside research materials and jointly produced interpretation. Later in 2025 we will continue to work with Holly to activate this with an audio tour, which includes the voices of community partners, a performance and film.

Reflections by Rosie Gnatiuk, Costume Curator

Holly’s generous and expert facilitation of workshops with communities through her work with 422 Arts (a community-led arts group) and residents local to Platt Hall (a sister venue to Manchester Art Gallery in south Manchester) has been a valuable learning experience for the team. It has activated critical self-reflection and moved us towards more open conversations around the history of the collectors and the collections held at Platt Hall which form the resource and ethos that underpin its development.

During the ‘Textiles & Tall Tales’ workshop, Holly invited reflections from participants, exploring how memory and narrative shape collective history. She carefully documented conversations around cotton, expertly creating a space for a democratic approach through bringing together a range of perspectives to develop oral history recordings. This created a ‘way in’ through sharing personal connections to cloth and thinking about the links between fabric, industry, empire and local memory.

Through these workshops, framed by Holly’s research and residency, the team at Platt Hall and residents were more able to critically and openly explore collections held there – including patchwork samples and 1830s printed dress and pattern books – thinking about the histories of exploitative labour inherent in cotton.

One participant reflected:

I am very interested to discuss and excavate, not literally but through ‘dialogue’, the provenance of gallery objects, how they came to be, and the meaning attached to those who created them, especially in relation to slavery and the industrial labour force with associated exploitation. Including intergenerational trauma and memory, as they carry on down the generations. This is a very complex theme and needs further investigation.

Another area of learning was to reflect on and address the lack of visibility and accessibility of the pattern books that sit within the unaccessioned archives held at Platt Hall. These illustrate the extent of Manchester’s cotton print development and trade, fuelled by exploitative labour. The books are a key resource that have been on the periphery of the collection and yet are central to it. Holly carefully studied and explored every sample of textile and design within the pages of every book, and so identified rare examples of woven Manchester check, also known as ‘Guinea cloth’

This research is being drawn together to create an 1850s-style printed cotton dress and elements. Holly is working with her mother, a former costumier, to create this. It is a manifestation of the many threads of research and connections that Holly has made throughout her residency. The dress embodies the presence of African American abolitionist campaigner Sarah Parker Remond, referencing the Royal Manchester Institute and the Athenaeum where Remond spoke. Holly activates the archives, incorporating the print of woven check from the pages of the pattern books and the design of book end papers of Royal Manchester Institute subscribers’ logbooks held at Manchester Central Library.

The 20/20 project offered a valuable opportunity to work with an artist who holds a wealth of experience, knowledge and insight. It has been a privilege to explore the richness of Holly’s skills and many layers of research within her body of work as it has developed and to understand the critical connections she has made.

Reflections by Kate Jesson, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art

Holly’s research has made visible unaccessioned, undocumented, unseen and unused archives. We are now documenting these textile ledgers, pattern books, cotton bale labels and samples of West African textiles so they are more easily accessible. Our new online collection search and updated collections database will increase public access to multiple stories, acknowledging this labour and helping to communicate and distribute the stories. This, of course, comes with new issues to work through, including hierarchies of voice, and editorship versus censorship. The work is raising interesting questions about traditional collection systems of value, use and display. It is feeding into our Collection Management and Collection Development policy reviews that underpin the way we work.

Holly is also weaving these undocumented archives back into relationship with other objects and artworks on display. She is authoring an audio tour guide of these new and revitalised connections. Disrupting the colonial nature of a traditional gallery tour, it will be expansive and reparative, sharing knowledge and giving voice to our 422 Arts and Global Threads colleagues.

We will be sharing this work more publicly across our gallery spaces from March 2025. Holly’s research will weave through many areas of work across the gallery, impacting how we present, talk about, document and share the collection, as well as collaborate with and learn from others.