There is something like time travel in the way that Habib Hajallie layers an artwork from 1981 over a text from 1938, and a drawing of himself as he looked last week. “I’m creating a moment in time that doesn’t exist”, he says, “[but] that has relevance for today.” [1] In a way it is similar to building a collection, with artworks and references from different eras brought together to be considered on the same aesthetic plane.

As an artist Hajallie is captivated by people. He is continually researching and discovering new subjects to draw, whether that be individuals from ethnically diverse backgrounds that have been omitted from traditional portraiture, or figures from art history that came before him. Each of his hyper-realistic ballpoint pen portraits is a way for him to discover his subject(s) as well as privilege them, to unearth something new and show it off to the light.

Born to Sierra Leonean parents in South East London, Hajallie has always been frustrated at the lack of diversity in art and culture, and sees portraiture as a means to “rectify the historic lack of visibility of figures from ethnic minority backgrounds”. [2] This has seen him draw the artist Sir Frank Bowling; the first black mayor of London, John Archer; and the first black woman to be a governor of the British Broadcasting Corporation, Dame Jocelyn Barrow. Ball point pen is his medium of choice due to its versatility as well as its accessibility. “It’s not expensive like oil paints”,’ he says, “I’m interested in breaking down the barriers [to art], and elevating an everyday medium.”[3] He has also traded the traditional white ground for antique books and maps which he buys on eBay. Drawing over texts like R.S. Lambert’s 1938 treatise, ‘Art in England’ allows him to add another dimension to the work, creating a new context for his sitters that takes them out of their current reality and into a fictional space he is creating on the page.

As well as portraits, Hajallie has also became known for his self portraits, using his own likeness to communicate how issues he is passionate about impact him at a personal level. In his 2020 triptych, ‘Where are you really from’ Hajallie imagined himself as the stereotype of the Black man, a Middle Eastern man and a white man. He exaggerated the caricatured features of each ethnicity—the Black stereotype looks aggressive, the Middle Eastern man, suspicious—to “convey the nuanced racial prejudice that [he has] experienced” as a “racially ambiguous… mixed race man”. [4] By embodying the racism levelled against him, Hajallie shows it to be the farce that it is.

In 2022/23, Hajallie completed a fifteen-month residency at Pallant House Gallery as part of 20/20, a project run by UAL’s Decolonising Art Institute, which encouraged him to investigate what it means to be British and the nuances within Black British history. Spending 12 months delving through the gallery’s archive gave Hajallie an insight into the lives of three of the main collectors who bequeathed to the collection, and made him consider the role that collectors play in the art world. “They were really friends with the artists they supported… like Colin St John Wilson”, he says, referring to the architect who bequeathed his collection of post-war British art to Pallant House Gallery in 2006. “He had deep, profound relationships [with the artists he collected]… [he really] blurred the line between artist, friend, patron and peer.” [5] Indeed, most of the artists in St John Wilson’s impressive collection were friends of he and his wife, American architect MJ Long, Lady Wilson. In the handwritten correspondence held at the Pallant House Gallery archive, artists like Eduardo Paolozzi, Richard Hamilton, Peter Blake, R.B. Kitaj and Michael Andrews address him by his nickname, Sandy.

This relationship between artist, collector and gallery is explored in Hajallie’s new work, ‘The Large Collectors’, 2023, made as part of his residency at Pallant House Gallery and acquired by the Gallery. In the foreground are the aforementioned collectors who gifted their collections to Pallant House Gallery: Reverend Walter Hussey, Sir Colin St John Wilson and Charles Kearley. In the background, stands Hajallie, arms folded with his back to the viewer, framed by the interior of Pallant House Gallery. The composition of the figures is borrowed from the Cezanne lithograph ‘The Large Bathers’ (‘Les Grandes Baigneurs’), 1898, which features three male bathers in the foreground, and a fourth in the background, looking away from the viewer. Hajallie chose to use this composition, as ‘The Large Bathers’ was one of the works that helped distinguish Charles Kearley as a serious collector and is now a key work in the Pallant House Gallery collection. This poses interesting lines of enquiry for Hajallie, such as the way that taste operates in showing art, the inevitable bias upon which collections are built, and how artworks can be instrumentalised as status symbols.

At the heart of this set of concerns is the question, what does it mean to leave a private collection to a public museum? Is it a selfless act breaking down barriers to art, or a self-serving endeavour solidifying one’s legacy? This dichotomy figures heavily in the history of the founding of Pallant House Gallery, which was established when Walter Hussey left his sizeable and varied collection to Chichester District upon his retirement in the late 1970s. On his request, the Queen Anne townhouse in the city centre was restored to display his artworks, and Pallant House Gallery opened in 1982. Similarly, when Colin St John Wilson left his collection to the Gallery in 2006, a contemporary wing had to be built to house it, [6] expanding the gallery yet again.

The gifting of private collections to public museums is one way in which artworks are canonised, and while this does enable access, it is also based on a relatively small number of people’s opinions. This seems to be something Hajallie understands, and is perhaps why the context around the figures in his drawings has become increasingly important. In a new work made during his residency at Watt’s Gallery, ‘A British Hall of Fame’, 2023, Hajallie not only draws individuals he thinks haven’t had the recognition they deserve, but also a gallery space within the picture plane for their portraits to be displayed. Six figures that Hajallie considers to be great Britons are drawn in rectangles in the background of the image—John Agard, Sonia Boyce, Dave (AKA Santan Dave), Lubaina Himid, Paul Stephenson and Phyllis Akua Opoku-Gyimah. These ‘portraits’ are framed by a monumental arch, a nod perhaps to the neo-classical architecture typical of many major art museums. In front of this stands the artist G.F. Watts and the photographer Simon Frederick, who both experimented with creating their own ‘halls of fame’ in different ways. This framing of portraiture within a wider speculative environment, sees Hajallie play the gallerist as well as the artist and collector. He might not be able to rehang galleries, but he can draw the arrangements he’d like to see placed there.

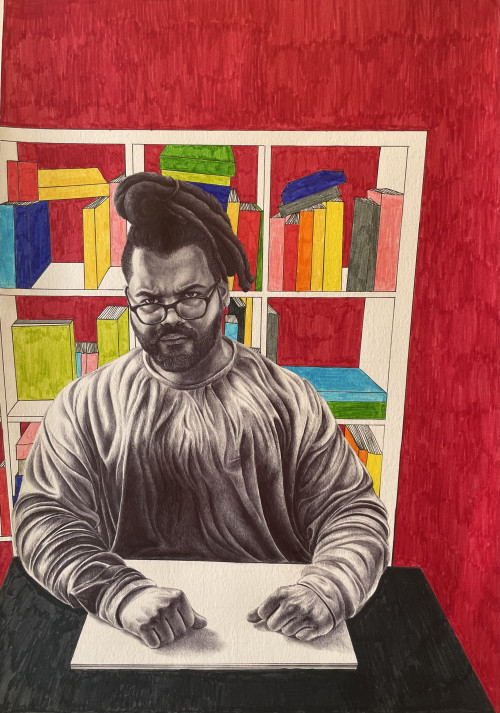

Any hall of fame is based on personal opinion, and Hajallie’s own bias is something he is keenly aware of. He was careful to title the work ‘A British Hall of Fame’, not a ‘Black’ British hall of fame as, even though the six figures he championed are black, he did not pick them because of their race. He also decided against calling it ‘The British Hall of Fame’, as it is not definitive, or objective. It is his subjective selection, just as a collection reflects a collector’s personal choice. In ‘A British Artist’, 2023, made during his residency at Pallant House Gallery, Hajallie compares his own interiority as an artist to that of another artist in the Pallant House Gallery collection, R.B. Kitaj. The drawing depicts Hajallie in front of his bookshelf at home, looking sternly serious. Behind him, yellow, pink and green books accentuate a vibrant red wall. The work is based upon the R.B. Kitaj painting, ‘The Architects’, 1981, which shows St John Wilson, his wife MJ Long and their children, Harry and Sal, in Kitaj’s studio (which Long designed). Hajallie saw both works as interruptions—in Kitaj’s painting St John Wilson looks irritated by the intrusion of the artist’s gaze, as if it’s not Kitaj’s studio but his own. In ‘A British Artist’ Hajallie looks upset at the disturbance to his work as an artist. The works call attention to the nature of portraiture, the figure behind the drawing board, and how their relationship with the sitter may or may not influence the art produced.

Hajallie describes his work as looking at what it means to be British and the nuances within Black British history, but there’s more going on in his practice than that. Since the Pallant House and Watt’s Gallery residencies he has started to unpick the mechanisms of the gallery system, looking at the interconnected roles the gallerist, collector and artist have played in art history, and how, if he really wants to empower the figures he is passionate about, where that empowerment might have to come from. Racial equality within British collections might be a long way off, but in the meantime, Hajallie has his pen, and his drawings act as blueprints for what he wants the future to look like.

[1] Hajallie, op. cit.

[2] Hajallie, op. cit.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Habib Hajallie, “About Me”, available at https://www.habibhajallie.com/about, accessed 27 September 2023.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Colin St John Wilson and his wife MJ Long also designed the new wing.