Introduction

Curtis Holder draws spirit. He draws not only the energy of the sitter before him but spirit, as in, the unseen. His drawings are divinations, drawing to the surface what is sensed, or felt, as clue or hunch, an instance of what the scholar Phillip Brian Harper terms ‘speculative rumination’. [1] In Curtis’s practice, talent, technique and time fuse with something tacit and tangible, yet of the ether.

Curtis is a channeller: a diviner of lines. Social anthropologist Tim Ingold writes of ‘how the two senses of drawing – as pulling threads and scribing traces – are intimately related’. [2] In terms of Curtis’s own line, or lines, I think of the ‘intimately related’ task of his artistry in ‘pulling threads’ and ‘scribing traces’ as two-fold: spirit and the politics of craft. As a writer and scholar of practice-based research and, specifically, autoethnographic study, in this reflective essay, I offer meditations on these two points. I do so with reference to Jacques Derrida’s concept of ‘hauntology’, [3] and the work of scholars extending the concept, such as, Christina Sharpe. [4] Further, in my essay, I incorporate fragments of journaling and draft poetic lines written in the black Derwent sketchbook, which Curtis kindly gifted me and the seven other sitters for his project.

Spirit

From the earliest of our conversations, Curtis and I have talked ghosts. From the woman in the green dress who sat, like comfort, at the edge of his bed during a period of childhood illness, to the women in my family who talk about the tangibility of ghosts as ordinarily as they do the living. Ghosts haunt our conversations. Ghosts haunt our friendship. Ghosts haunt my experience of sitting for Curtis.

On the first morning of the two-day sitting period, Curtis and I talk about family lines. Mothers. Fathers. Illness. Death. I am not able, of course, to see the initial draft sketch of me as Curtis is drawing me, though I can hear the sound of what I will learn, later, is Blackwing Matte pencil upon 200g Fabriano paper. Mid-afternoon. We are about to take a lunch break. I ask Curtis if I can look at his first sketch of me. I am stunned. Staring me back is a mirror of someone I recognise immediately: my mother. My mother died 12 years ago. Curtis has never seen a picture of my mother.

Christina Sharpe’s study ‘On Blackness and Being’ (2016) is a meditation upon death, including familial death. Sharpe posits a prismed definition of the word ‘wake’. Wake, not just as in funereal ritual but

the track left on the water’s surface by a ship; the disturbance caused by a body swimming or moved, in water; it is the air currents behind a body in flight; a region of disturbed flow [5]

What underlies Sharpe’s definition of the word ‘wake’ is a ‘ghost word’: ‘trace’. The trace of Curtis’s Blackwing Matte pencil against the paper’s grain; the line’s disruption of deckle and ream; plumes of line tracing present tense and memory, until the past becomes an almost-touchable Icarus dream. Tomorrow, I will bring a photo of my mother with me to share with Curtis. Today, he has drawn what he cannot tangibly see, yet. Curtis cannot know, until tomorrow, how his sketch of me is awake to the frequency of the unseen. He cannot know, until tomorrow, the way in which his sketch of me, today, depicts the arch of my mother’s eyebrow; the sockets and shape of her eyes; the slant and height of her cheekbones – all the ways in which my mother returns.

Curtis and I take a selfie with Curtis’s emerging sketch of me behind us. I post it on social media with the following message:

[Social media post featuring photograph of Curtis Holder and Rommi Smith with Holder’s draft sketch of Rommi Smith, Curtis Holder’s archive]

What I don’t remember, until later, is that Curtis’s residency studio, in Leeds Art Gallery, is in what is formally known as the Motherhood Gallery.

Throughout the first day of sitting, I am awake to the traces of grief. The line of grief is a turbulent road disrupting its way through the daughterly state. Over lunch, at Eastern Oven, a Leeds Market stall serving Turkish-Syrian soul food (a stall which welcomed me in the earliest days of losing my mother; the ritual of my visits a comfort whilst mourning; the welcome of a cardamom coffee placed at my elbow each visit) we talk about my father. A man haunted by the Biafran War; a man who made strangers of his children – he is a jigsaw puzzle of a man whom it has taken my life, thus far, to understand.

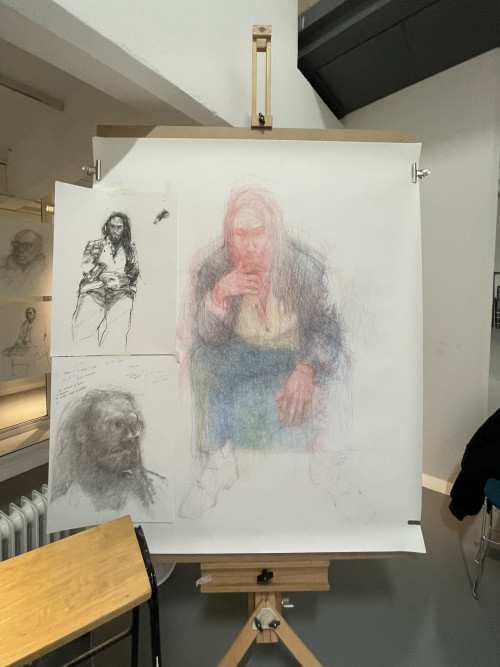

When we return to Curtis’s studio, or project-workshop, Curtis begins layering the morning’s drawing of me with more detail. I talk as he works, studiously focused, occasionally raising his hand, using the pencil’s breadth, one eye shut and the other open, to assess distance and measurement. I talk more. Deeper. Me, barefoot, running through decades, backwards, to stand in the doorway of childhood.

At some point in the talking, I realise that each word is a dark coin dropped into the well of epiphany: this space is a confessional. I’m taken aback. Things are emerging from the box marked ‘private’. I ask Curtis if I can look at the drawing again. What startles me is that, in terms of layering, the morning’s drawing has now morphed in its energy and physicality. There is someone staring back at me, someone whose energy I recognise as an intertwining of anger and thunder: my father.

The politics of craft

In Derrida’s book ‘Specters of Marx’ (2006), he states that if we are to dialogue with the revenant, or ghost, then it is in the name of justice.

If I am getting ready to speak at length about ghosts, inheritance, and generations, generations of ghosts, which is to say about certain others who are not present, nor presently living, […] it is in the name of justice, of justice where it is not yet, not yet there. [6]

Extending Christina Sharpe’s reconceptualisation of ‘wake’, to think of the lines in Curtis Holder’s portraiture, I reflect on the track the Blackwing pencil makes, moving against the big white sea of the Fabriano page. Wake, not just as in a night-prayer vigil for a dead body, but an evolving light illuminating the creative body. For the visual artist, just as the poet, this wakefulness is aubade-as-light, as in, to be ‘awake’, [7] or in a state of awakening – feeling a profound and resourceful sense of alertness, including being politically awake.

Sharpe’s ‘wake’ intersects with Derrida’s ‘hauntology’, and his rationale for dialoguing with ghosts: ‘justice’. Justice is tacit to Curtis Holder’s practice and his choices in artistic direction; from his exhibition ‘Curtis Holder: Portraits of Brotherhood’ (Guildford House Gallery, 6 July – 28 September 2024), to his appointment as Artist in Residence at Leeds Art Gallery as part of the 20/20 project. His lines move absence into presence. His lines disturb and disrupt absence, the Black line challenging erasure and oversight by centring what is socio-culturally and institutionally, all too often, unseen.

Curtis knows the spotlight of rising recognition, his talent garnering him awards including Sky Portrait Artist of the Year (2020) and The John Ruskin Prize (2024). Yet, he sees and centres subjects which are all too often placed in shadow; people often outside of dominant, idealised Western definitions of normative narrative bodies. Curtis centres Black and Brown people, Queer people, women whose bodies do not adhere to oppressive, restrictive ideas of normative beauty, working-class masculinity and people working behind the scenes of major theatres. All these are not mutually exclusive, but intersectional – and gloriously so. Central to Curtis’s craft is an embodied, tacit, decolonisation aesthetic, luminous in its practice-based definition and implicit understanding of decolonisation, the term not requiring curatorial whitesplaining.

Curtis is an observer. His presence, a scribing witness on the edge of spaces, where he intuitively records the energy of the space and the bodies within it, in line form. This is how I first met him. In October 2023, Curtis was invited by Leeds Art Gallery staff, as part of his residency, to draw and archive aspects of the series ‘Temples to These Women’ (2023). [8] I curated this participatory, community-focused celebration of Leeds Black and brown women’s vocality, working to co-facilitate it in collaboration with a small team of Leeds-based, largely Black and brown women artists. [9] The project was a response to Sonia Boyce’s exhibition ‘Feeling Her Way’ (British Council, 2022). Professor Boyce’s exhibition centres the voices and talents of women artists of Black heritage (including Poppy Ajudha, Jacqui Dankworth, Sofia Jernberg, Errollyn Wallen and Tanita Tikaram). It won the Golden Lion Award at the Venice Biennale.

With a quiet, sensitive focus, Curtis drew the project’s vocal improvisation session, led by sisters Annette and Paulette Morris, otherwise known as reggae anthemists Royal Blood. Beloved and revered vocalists, songwriters and musical activists, they worked as collaborators with, and backing vocalists for, many of the music industry’s prominent ‘stars’ of the 1990s and 2000s. Curtis’s improvisational sketches of their workshop not only archive the energy of the room, and the dynamic between Annette and Paulette as facilitators (their workshop attendees rapt and spellbound at theirs and the room’s collective sound), but those drawings are now an archive in ways none of us could foresee. Annette died suddenly in July 2024. Curtis’s improvisational sketches of Annette and Paulette’s workshop in October 2023, now become an archive which has become even more precious in its meaning. Curtis’s drawings are an archive of the spirit and strength of Annette and Paulette’s love, as sisters, their heads and voices raised to the rooftop.

[Photograph of sketch of Annette Morris, 2023, Curtis Holder. Courtesy of the artist]

[1] Philip Brian Harper, ‘The Evidence of Felt Intuition: Minority Experience, Everyday Life and Critical Speculative Knowledge’, in E. Patrick Johnson and Mae G. Henderson (eds.), ‘Black Queer Studies: A Critical Anthology’, Duke University Press, Durham, NC, 2005, p.108.

[2] Tim Ingold, ‘Lines: A Brief History, Routledge, New York and Oxfordshire’, 2007, p.129.

[3] See Jacques Derrida, ‘Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International’, Routledge Classics, New York, 2006.

[4] See Christina Sharpe, ‘In the Wake: On Blackness and Being’, Duke University Press, Durham, NC, 2016.

[5] Ibid., p.3.

[6] Derrida 2006, p. Exordium xviii.

[7] I am aware of the derisory, puerile ridiculing of political awareness and respect by the political right and the weaponisation of the term ‘woke’. This essay speaks back to such derision.

[8] Partly funded by Leeds Inspired, Leeds Art Fund and Leeds Art Gallery, the event was hosted by Leeds Art Gallery and supported in kind by Little Black Megaphone, Airstream Events, Lazenby Brown, Duke Makes and my own company 125th and Midnight.

[9] JoJo Kelly, Christella Litras, Kamal McDonald, Paulette and Annette Morris, Dr Lara Rose, Waqar Shah, Ciara Simms, Jason Hird and workshop attendees.