There is an engraving by François Denis Née produced as an illustration for Jean-Benjamin Delaborde’s song ‘Love, Conqueror of Reaso’, published in Paris in 1773, that depicts a female nude’s attempt to take hold of a statue of Cupid stood on a plinth in a temple. She throws herself towards the statue but the winged youth dodges out of the way. As the woman reaches outwards and upwards towards the living statue of love, another allegorical statue, a female representation of wisdom, crashes to the ground beside her and breaks into pieces. In one sense, this is a harmless and sentimental picture with the theme of ‘the irrationality of amorous passion’, [1] but, at the same time, it is a revolutionary image that presents a dream-like vision of the collapse of the ancient order of duty and the birth of the modern world of feeling. This story of the transition from one society to another, only six years before the French Revolution, is told through the contrast between an unwanted, broken statue and a desired, living statue.

Yuen Fong Ling’s 20/20 commission for Sheffield Museums Trust tells stories about real, potential and imagined social change through staged interactions with the museum’s’ collections. One of the reasons why it is possible for this body of work to reflect on social change while focusing on artefacts rather than social action directly, without resorting to allegory, is that contemporary events have highlighted the politics of objects. It is only recently that headlines are being made by the longstanding campaigns to repatriate colonial treasures and to remove the memorial statues of historical figures, such as Cecil Rhodes, Edward Colston, Robert Milligan and Robert Geffrye. Today, it is almost impossible to reflect seriously on the museum form of the collection in general without considering the ‘diaspora of things’, which began with Napoleon’s ethnographic programme in Africa, cultural appropriation and the colonial categorisation of non-Western objects as anthropological.

In Ling’s performances and videos, objects become a kind of microscope through which the otherwise invisible social structures and the hidden logic of history can be sensed. He does not show these structures and histories or tell stories about them in the way that the feminist artists of the 1970s used text and voiceover to disclose what was latent in the photographic document. Ling stages an encounter between a body and a thing that is emotionally charged. As such, the viewer is not asked to see or know what is usually hidden from view when looking at the object. Rather, the viewer feels anxious or elated, uncomfortable or liberated, unsettled or joyous, crushed or encouraged, perhaps. Whatever these feelings are, or whether they are aesthetic or cognitive, ethical or political, they locate the object and its context within a specific social history of things, bodies, spaces and feelings. How you feel when you look at these objects and these bodies tells you something about your relationship to the histories and social systems that brought them together in this space.

This begins with the emotions of the performers – Ling invited several, each bringing a specific physical practice, to respond to objects in the collection. Their performances are rooted in other contexts and so the museum and its world can appear foreign, uncongenial or even hostile. So, what appears in the video documentation as a liaison between a body and a thing is also, on further reflection, a coming together of the various worlds to which these bodies and things belong. And just as each object might belong to two or three worlds (the museum, the private collection and its original context of use), the performers carry with them more than one ‘milieu’. Alongside the ‘milieux’ of race, gender, sexuality and class, the performers carry with them the specific milieu of their practice: circus, nightclub, cabaret, TV, theatre, mixed martial arts, Tai Chi, etc. In one sense, these milieux are carried within the performers by association and by virtue of biography, but they are also present in the museum via their bodies, their muscle memory and the values of their practices.

I want to think about these videos through a comparison with the videos we all saw of the toppling of statues during Black Lives Matter protests. Ling makes beautiful videos of a more poetic liaison with public objects. He turns his attention to these museum objects by virtue of a double displacement. Literally, therefore, the action of Ling’s work is displaced from the street to the museum. More importantly, though, the focus on the removal of monuments of slave-owners is shifted to a focus on objects extracted from their sites of use. The museum object is a scaled-down monument. And, like protestors climbing on or pulling down a memorial statue, the performers breach the distance that the aura of valuable public objects requires. This staged proximity plays on the anxiety that has been lodged inside us by the museum complex: not to touch, not to get too close and not to break the exhibits. Armed white supremacists in the United States, who responded to the toppling of statues after the murder of George Floyd by guarding controversial monuments, took up a similar proximity to auratic objects but, by contrast, they sought to reinforce the aura by standing between the statue and the crowd.

Ling’s redirection of our gaze from the statue to the museum artefact and, thereby, from a collective act of removal to an improvised act by a performer, does not dilute the affective charge of encountering public objects, but intensifies it. Abstracted from the more immediate conflicts of the street, the encounters between bodies and things that are staged in Ling’s work sublimate the emotional charge of the memorial sculpture by condensing the political content of history-making into a tightly framed montage of portraiture and still life. Stripped down to its core, feelings that are usually in the background of historical events are brought to the fore and into focus. So, just as the decolonial project is not halted by campaigns to decolonise the curriculum, to decolonise the university and to decolonise the museum, the focus on the affective dimension of the relationship between bodies and objects deepens, extends and completes the critique of a toxic tradition. In this way, Ling’s work is also a proposal for a new kind of museum that does not sacrifice aesthetics and feeling in striving towards a critical relationship to its troubled and troubling heritage.

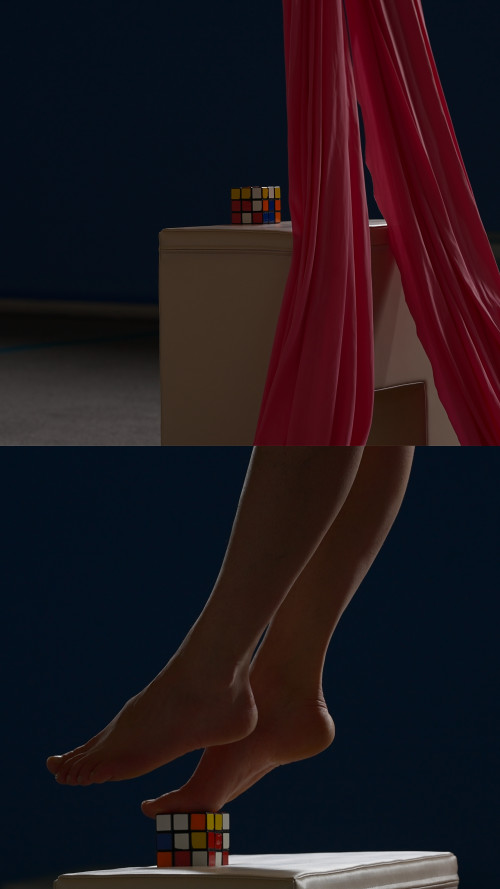

It is significant that Ling’s intervention in the museum started out as a tale told on a plinth on the street. In public spaces, the plinth is a miniature museum in the sense that it signifies the publicness of that which it supports, elevates and protects. In Ling’s work, however, the plinth was unusually mobile. Ling and a handful of participants walked around the streets of Sheffield carrying a plinth that they used as a stage and a platform. Ling produced a series of works, part performance and part public artwork, collectively titled ‘The Human Memorial‘. ‘Scaled up‘, the artist says, “the plinth becomes a proposal for the public to step up on the structure and be the “monument”’ Documented in the film ‘The Empty Plinth’, 2022, Ling’s recent work belongs to the genre that Michael Hatt, thinking of artists such as Tatsurou Bashi, Sophie Ernst, Hew Locke, Krzysztof Wodiczko and Gary Kirkham, and Hadley+Maxwell, has called the ‘counter-ceremonial’ and what Mechtild Widrich named ‘Performative monuments’, especially the process that Widrich calls the ‘rematerialisation of public art’. In this series of interventions, the historical burden of the physical presence of the monument is dissipated by focusing on the organisation of bodies that assemble around and on them. Instead of thinking that cenotaphs and other monuments are primary and, therefore, that the bodies that assemble around them are secondary, Ling simultaneously widens the scope (by including what is peripheral to the monument itself – i.e. the social uses of monuments) and zooms in to the lived experience of public space.

Moving the inquiry from the street to the museum, Ling turns the ‘performative monument’ and the ‘counter-ceremonial’ into an act of institutional decolonisation. Glen Ligon, a gay African American man from a working-class family, made the same journey in his work, ‘Condition Report’, from 2000. The work revisited a painting he had made in 1988 of a white rectangle with the words ‘I AM A MAN’ in black enamel. The black and white painting was rooted in documentary photos of the placards carried by sanitation workers in Memphis in 1968, striking after the death of two black colleagues. For ‘Condition Report’, Ligon had a photograph of the painting inspected by Michael Duff, a paintings conservator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The conservator provides a ‘condition report’ on the quality of the image – and perhaps, by extension, the condition of race, gender, sexuality and class oppression in the United States – by circling blemishes. The museum, represented by the conservator, proposes to eliminate all the damaged areas but, in doing so, highlights or underlines every instance of damage by circling it and annotating it. The life of the painting is registered through the accumulation of damage.

The common starting point for Ligon and Ling is the acknowledgement not only that the museum is a complicated bequest (like inheriting debt, the museum represents a legacy that tells a shocking, uncomfortable tale about the past), but also that the museum is not a space of withdrawal from politics, but a site of struggle. One of the ways in which the museum is being transformed today is to ‘call attention to, and work to un-silence, the systematic muting of the colonial violence and harm that these collections often emerged out of’, [2] to use the words of Wayne Modest, the Director of Content of the National Museum of World Cultures in The Netherlands.

What was lost in the 20th-century archive was not only the original communities of the object but also the labour of museum employees. We get a glimpse of the latter, today, when galleries and museums post pictures on social media of displays as works in progress. Ling, whose primary interest is in the bodies that assemble around objects, extends this new revelatory style of documenting behind- the-scenes activity of museum work by recording the moment when curators pass objects to performers. Since the aura of a museum collection is felt more by visitors than employees and was absent for the original users of things, this is a symbolic act that cuts to the quick of the affective content of the encounter with a thing designated as public. The actual handover can be relaxed or anxious, but the passage is fundamentally dramatic because the object re-enters the world. By demystifying the object and the techniques of its institutionalisation, the transaction between museum workers and paid performers proposes a wider relinquishing of the professional enclosure of the historical commons.

Unboxing a de-socialised object and handing it over to a fire dancer or rope acrobat is emblematic of a reversal of the museological capture of life. This is what Robert Smithson had in mind when he compared the gallery to a prison cell and a coffin. It is also what initially gave Carl Andre’s use of firebricks a radical connotation. Originally selling the bricks back to the building merchant after he had exhibited the work, thus returning the object to use, Andre might use different bricks to show the same work in several locations. When the Tate purchased ‘Equivalent VIII’, however, they stored the ‘original’ bricks in custom-built boxes. For Ling, however, the opposition between the art object and the object of use is better understood not by tracking the circulation of objects, nor even by replacing the contemplative object with an art of utility, but by speculating about insurgent modes of assembly and the formation of counter-publics.

‘We Are the Monument’ exemplifies the condition of art in the era after the Arab Spring. Mike Davis observed that the Arab Spring was ‘a historical surprise comparable to 1848 or 1989’. [3] Like the Sandianistas before them, the occupiers of Tahrir Square not only inspired protestors into action but supplied them with a toolkit of twenty-first-century insurgency. It acted like a beacon for emancipatory movements around the world, spurring on others to take to the streets, develop collective counter-powers through place-based activism, to organise themselves through digital ‘networks of outrage and hope’ [4] and to use social media to cultivate affective counter-publics and communities of care. After the Arab Spring and Occupy, the history of public art has to be reassessed so that, for instance, Lorraine O’Grady’s street performance, ‘Art Is… (Cop Framed)’, 1983, can be seen in a new light. O’Grady and 15 African American and Latino performers carried empty picture frames as a gesture of inclusion to the mostly black participants.

Like O’Grady, Ling’s work uses a convention of artistic elevation to recast performing bodies as subjects and agents of art. At the same time, his work resonates with Sonia Boyce’s project at Manchester Art Gallery in which she responded to young female museum workers who were unsettled by John William Waterhouse’s painting of semi-naked girls in a pond by removing it from display in order to ask questions about museum decision-making and public perceptions of the collection. It also relates to Carlos Martiel’s ‘Monumento II’, a performance consisting of the artist standing motionless on a pedestal, located in the museum’s rotunda. Handcuffed, and nude, the artist is a monument to the anti-black racism, white supremacy and racial violence. Ling’s work also resonates with the work of David Hammons, not only in the directly comparable performance, ‘Pissed Off’, of the artist pissing on a public sculpture dedicated to the Transport Workers Union in New York, by Richard Serra, one of the most successful and renowned white artists of the day. In yet another sense, Ling’s work reimagines Bruce McLean’s hilarious and pivotal performance of the artist posing on a plinth, which put the living body in the place of sculpture, as a poetic image of a post-Arab Spring technique of social change.

This takes us back to where we started, six years before the French Revolution. Living statues were common in Rococo painting. Both Jean-Honoré Fragonard and François Boucher depicted statues as characters who interact with the main figures represented in semi- rural scenes of romantic intrigue. Look at the statue on the left edge of Fragonard’s famous painting ‘The Swing’ from 1767 in which a woman is swinging from a tree by a rope held by her husband behind her while she is tossing her shoe to a younger man hiding in the undergrowth in front of her. Eros, perched on a plinth, looks down at the scene and holds a finger to his mouth, as if the secret liaison could be discovered at any time by a sigh or a giggle.

There is a similar moment in one of Ling’s videos that stages an encounter between the living and dead monument. A fire performer is imitating the fire that they are not allowed to use within the museum. As the curator hands over the object, the fire performer calms down. It is not clear whether the museum object extinguishes the fire of the living being, or if the living being somehow takes on the stoic quality of the object as it passes from the museum to the body.

[1] Andrei Molotiu, Fragonard’s Allegories of Love (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007), 37.

[3] Mike Davis, ‘Spring Confronts Winter’, New Left Review, 72, November–December 2011, 7.

[4] Manuel Castells, Networks of Outrage and Hope (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012).