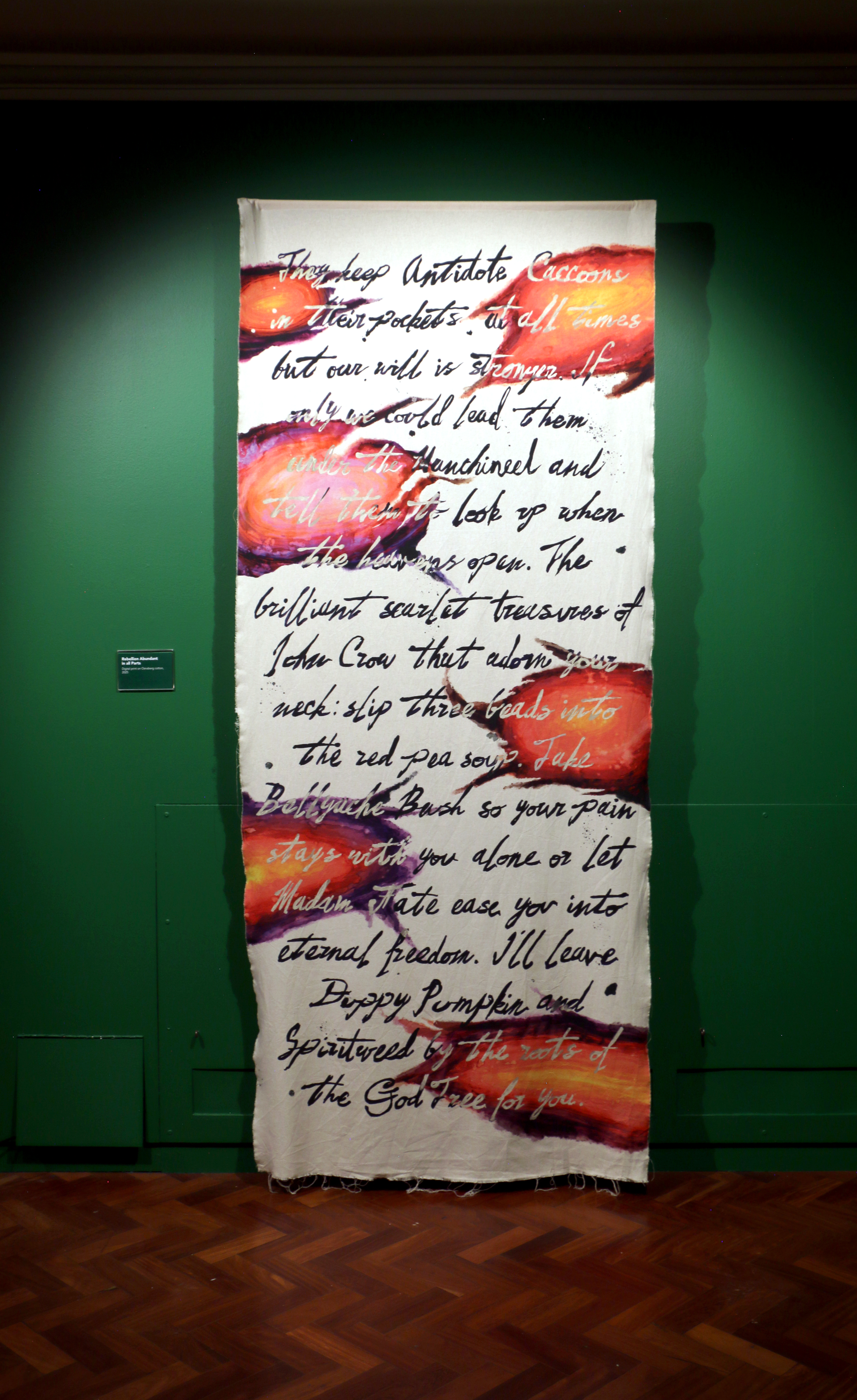

Photo courtesy of the artist: Jessica Ashman

I’m currently in residence with Bristol Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG), responding to a few archival collections. One being a series of watercolour paintings of the flowers and fauna of Jamaica, from Rev. John Lindsay; a Scottish Priest, serving the Church of England. He was active in Jamaica during the 1700s, having married into a plantation owning family. Another collection is of dried flowers from Jamaica dating back to the late 1700’s by Dr. Arthur Broughton. I’ve also been looking at various artefacts surrounding the BECC (British Empire and Commonwealth Collection), specifically a series of letters from a Pharmacist called John Small, who moved to Jamaica in the 1850’s to aid his cousin run a medical practice but ended up establishing a coconut plantation. These letters document his life in Jamaica.

Photo courtesy of the artist: Jessica Ashman

Photo courtesy of the artist: Jessica Ashman

Both of these archives speak to something I’m intensely curious about; the idea of abundance, paradise and “utopias”. For Lindsay and Broughton, Jamaica seemed to be a potential foot-in-the door to the fame of the botanical academic world. Linsday appealed to the House of Assembly in Jamaica to get his drawings published and failed. Broughton was more successful, with an indigenous Jamaican Orchid named after him (Cassia Broughtonii ). For Small, Jamaica was a land full of business and therefore, financial, opportunity. One of his letters back home exclaimed Jamaica was a land “of milk and honey”. My focus at BMAG was to look past the colonialist’s ideas of abundance and think of how the flowers and vegetables drawn and discussed were used as tools of rebellion and resistance for the enslaved people of the island. How did the wilds of Jamaica create ‘abundance’, paradises and ways of offering hope and freedom for the oppressed, if at all?

-

Photo courtesy of the artist: Jessica Ashman -

Photo courtesy of the artist: Jessica Ashman

Working with BMAG with this vision in mind has been an overwhelmingly positive experience. My ideas were embraced whole heartedly by the staff I worked with, when I was concerned how ideas rejecting the might of colonialism would be received in a large institution. Curator of Art, Julia Carver, and Steven Bradley, Exhibitions and Display Manager have been guiding me through this research journey, offering advice without any pressure into a pushing a narrative I might have been uncomfortable with. Working with Rhian Rowson, Curator of Biology, has been a particular joy. Rowson’s energy and enthusiasm into decolonising the archive is infectious and has been immensely helpful in understanding the often confusing world of biology archives. The hospitality and help of Jayne Pucknell and Frances Davies over at the BECC department was pivotal in exploring how Bristol’s Caribbean carnival, St. Paul’s Festival, could connect to themes of resistance and Jamaican folklore in my research.

Photo courtesy of the artist: Jessica Ashman

I can’t speak to the career possibilities of the 20/20 residency just yet; I’m still in the making stage! The results of my research so far are currently being formalised into the physical. I am creating several installation pieces that use silk paintings, acrylic, animation as well as a soundscape and series of performances. The current plan is for the exhibit to open in Feb 2025.

However, I can speak to how this residency has made me realise the importance time and space gives to process. Like most emerging artists working today, a scarcity mindset prevails over my practice. There’s never enough time. Never enough space. Never enough support. Never enough money! However, whilst this residency hasn’t exactly solved all of these perennial issues it has given me the grace to explore process in a way I have never have before. This space has allowed me to dissect the connections between my making and the research in a way that feels meaningful and nourishing to my future practice.

Photo courtesy of the artist: Jessica Ashman

Finally, as someone whose project is really trying to speak to the power of human resistance through nature, the 20/20 residency has also opened my eyes to how archival re-imagining can feel like a quiet rebellion. Delving into the stores of BMAG has really opened the possibilities to how many ancestral stories are hidden or need to be re-imagined and how the light of archival importance must be shone elsewhere. To be part of this resistance, pulling these stories out of the dark, is an honour and a privilege.

Photo courtesy of the artist: Jessica Ashman

Photo courtesy of the artist: Jessica Ashman

Partner Reflection

Bristol Museum & Art Gallery

Steven Bradley, Exhibitions Manager

Julia Carver, Curator, Art

Frances Davies, Documentation, BEC

Rhian Rowson, Curator, Biology

The murder by US police of George Floyd in May 2020 and the Black Lives Matter demonstrations that took place around the world during the Covid-19 pandemic made discussions around decolonisation within museums and galleries all the more urgent. At Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, staff took part in decolonising workshops that summer. Then the statue of Edward Colston, the Royal African Company official responsible for the sale and transport of hundreds of enslaved African people to the Caribbean, was toppled at a BLM march after a memorial vigil for Floyd. The questions raised by the fall of the Colston statue foregrounded not just who is memorialised but who makes the figures carved in stone or cast in bronze for future generations. The gesture helped us to recalibrate the debate towards an art of inclusivity, away from historically lauded, singular figures whose ‘achievements’ had long been under scrutiny, and grand aesthetic gestures. In the immediate aftermath of the statue’s toppling Bristol Museum & Art Gallery was approached by a patron to develop a commission to mark the BLM campaign and pay tribute to those whose lives were taken. Bristol artist Jasmine Thompson was selected to do this work. Then Dorothy Price, formerly at the University of Bristol and now at the Courtauld Institute, sent details of the 20/20 project, which seemed perfectly in tune with the work the museum was doing, and a wonderful and ambitious opportunity.

We supported the UAL application to Arts Council England, with examples of our activity plans and Bristol Museum & Art Gallery’s own activities around decolonisation. Through the application process we had the pleasure of selecting from many artists we would not have otherwise encountered. It was a tough choice but we are delighted to have chosen Jessica Ashman, a multi-disciplinary artist working with animation, moving image and performance.

Jessica began work on her research in 2023 and, so far at the time of writing, has concentrated on this process, first meeting Jayne Pucknell and Frances Davies at Bristol Archives who care for the British Empire and Commonwealth (BEC) Collection and Rhian Rowson, our Biology Curator. She has also been working with Steve Bradley, our Exhibitions Manager, who in 2022 worked on a major youth project exploring decolonisation in the museum’s history collections. This text includes contributions from everyone involved.

The BEC Collection is a rich source for anyone working on decolonisation. Jessica spent some time in the store looking at some of the objects, with a particular focus on material connected to carnival, masquerade and the plant life of Jamaica and the Caribbean region. Amongst other things, she viewed costumes from both the Notting Hill and Trinidad carnivals (including a massive Black Madonna figure), items from the Junkanoo festival, along with watercolours by Jamaican artist Dorothy Henriques-Wells.

Jessica explored the 1780s Jamaican herbarium (pressed plants) and manuscript on plants grown on the island, including those brought in to be grown to provide food in the 1750s. These herbaria and manuscripts on plants in the eighteenth century were produced as a personal quest by their creator to gain recognition in the scientific field – a far from innocent endeavour. The knowledge within these books and herbaria was probably gained from Africans who had been enslaved. Not only were they not credited for their input, but the reason for the manuscript and herbarium’s creation was to fuel the British Empire’s economy. The study of certain foods and how to grow them was driven by the desire to increase food production and thereby to increase wealth and slavery. The collection raises the question of naming species and ownership – highly symbolic in the context of colonisation and enslavement. This is where Jessica has developed her deep focus and we believe this poses new questions, of the museum and for our visitors. It is easy to see colonial connections in art or archives, but our natural history curators have been working on decolonising the science collections and Jessica’s work will bring some of this to light.

Jessica was initially interested in this collection because she had been inspired by Testimonies on The History of Jamaica Vol.1 by Zakiya McKenzie of which we had a copy on show when we met, therefore the fit felt perfect from the beginning. This collection was ripe for exploration due to her interest, heritage and green fingers. Jessica’s creative talent was the right ingredient to explore the history of our eighteenth-century Jamaican botanical collection, bringing insight, pluralism and questioning to this collection.

The museum will be exhibiting Jessica’s work in February 2025 and our hope is to acquire the moving-image part of the installation. It is hard to reflect on a project that is now just beginning to come to fruition, but one key point comes from the title used by the UAL Decolonising Arts Institute for many of the network meeting workshops: Doing the Work. It is an ongoing process and Jessica’s work is a significant part of this.