Sometime before she passed away, a beloved aunty entrusted to me a cache of photographs. Loosely collected in an ordinary, nondescript office folder was what remained of our family’s archive, battered and torn prints of different sizes and from different eras. My grandfather, looking down high cheekbones, his mouth puckered around a cigarette. A black-and-white picture of my father and siblings, newly arrived in England from Sri Lanka, buttoned up in wool coats and bonnets for the first time, squatting between pigeons. Later, they would be splintered again around the world. When I look at the pictures now, I look for answers I can’t find.

What is so precious to me about this slim wad of pictures is not what is in the images, but the idea of the ellipses: the scenes I imagine before and after these events for which I was not present. Grasping at the ghosts and ineffable gaps that stymie a family history. Migration reduced our personal archive to this pitiful quantity, but all family albums leave lies in their wake, belie pain in pretty poses and ‘Sunday best’. In Bindi Vora’s ‘I Dreamt of Lost Vocabularies’, begun in 2010 and propelled over the last year of this 20/20 residency, the artist is interested in the acts of storytelling and remembering (or misremembering) that can be deployed in the making of images and objects. With lyricism and the most delicate touch, she considers how we can make up for such losses, the material proofs of our pasts. ‘A person without knowledge of their past history, origin, culture’, activist Marcus Garvey famously said, ‘is like a tree without roots.’

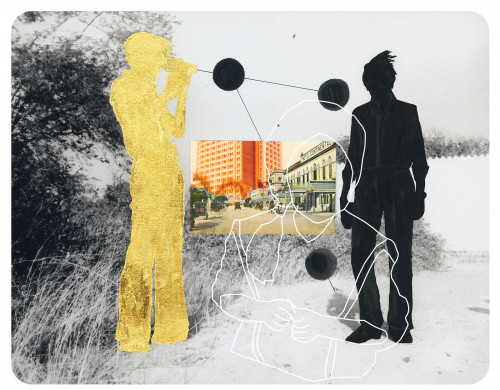

The central body of work that constitutes ‘I Dreamt of Lost Vocabularies’ is the series of photo-based collages, titled ‘Unravelling’. While Vora previously experimented with archival and found images and texts in her widely acclaimed ‘Mountain of Salt’ (2020–21, published by Perimeter Editions), here, her collages use coveted personal family photographs: ‘incredibly precious – the negatives belonged to my grandfather and father’. [1] Vora works with and on these images with thick gouache, pen and coruscating gold leaf, excavating the family image, removing the figures to insist on absence and the ineffable, half-effaced shadows of the unknown that percolate any family picture. Tracing a narrative through these family albums, as well as news articles and found materials of the same era, Vora uses gestures of mapping – circles and lines – in an attempt to find the through-lines of an entangled story, turning the vessels of memory of the photograph into a furtive fiction, open-ended and speculative. As the title implies, ‘Unravelling’ is an attempt to make known the knotty nature of identity, to understand the complexities of one family’s migratory journey in a viscerally intelligible and visually captivating way. Vora also adds silhouettes of her own image, cribbed from childhood pictures, to her grandfather’s pictures. It is a tacit act of questioning about her own place in this history, suturing herself into the narrative.

Vora’s mother’s family moved to Uganda in 1966, where they set up a small business, including a photographic studio, for a time. But by August 1972, 90,000 Asian people in Uganda were forced to leave the country following an expulsion order from the dictatorship of Idi Amin. In 90 days, the entire community was obliged to pack up and leave. ‘They could only take a handful of personal belongings with them.’ Vora’s family returned to Kenya, with some 2,500 other people of Indian descent, many of whom had come to Uganda as the result of calculated choices made by the British administration that governed Uganda until 1962, who brought them over to bolster a middle class and provide a buffer between the Europeans and the Africans. Amin declared he wanted to ‘return Uganda to Ugandans’ after British rule.

During the research Vora undertook, she read newspaper articles held at the McMillan Memorial Library in Nairobi. ‘I remember thinking about the undercurrents of racism, misinformation and the fear that 90,000 individuals must have faced at a time of transition, where beyond the community, the narrative has largely been forgotten.’ The layers of images and materials in these collages become a necessary visual strategy, ‘as I realise histories aren’t simply this full stop; they evolve, they have holes and often they lead you elsewhere’.

In 1984, Vora’s mother came to the UK to marry her Indian father. Vora was born in 1991. A new life for the family began in a new country, but with each new beginning ties to the past are loosened and sometimes left. ‘Unravelling’ is a way of rekindling connections – via photographs taken 80 years ago – between here and now to then and there. An act of preservation, as well as one of creation, making space within that history for the shape of the future, in a visual language that transcends words, as the family abandoned languages and adopted new ones – a common situation facing migrants who find themselves no longer able to communicate with previous generations. Vora recalls how, at school in the UK, she began to lose her connection to her paternal language, Gujarati. How do those gaps shape the passing down of stories and memories that become family folklore, embedded in a family’s understanding of itself?

The scale of Vora’s images – portable, handheld, like postcards or photographs that could be posted in an envelope – is evocative of departures, of lives made small by the threat of instability. Vora was inspired by a suite of miniature paintings depicting the Indian mutiny, around 1857–59, held in the collection at the Ulster Museum, Belfast. ‘There was no information about their original setting or context for production – but the particular people depicted included Maharani Jind Kaur, known as the Queen of the Sikh Empire, as well as Dhuleep Singh, known as the last Maharaja of the Sikh Empire, who was later nicknamed the “Black Prince of Perthshire”. Records of his presence in Northern Ireland were detailed in the book ‘The Irish Raj: Illustrated Stories about the Irish in India and Indians in Ireland.’ The shape of these paintings – with their rounded, smoothed-off corners – informed the ten works that make up ‘Unravelling’.

I was fortunate enough to see a presentation of these pieces from ‘Unravelling’ at Peckham 24, a contemporary photography festival in London, in May 2024, where Vora mounted the framed collages against a wallpaper, reproducing a newspaper image from 1972 showing a South Asian woman being marched onto a bus by the Ugandan army. ‘The gestures in themselves are so powerful – the pointing, the firm stance. As I read through these newspaper articles covering the expulsion, stories like this were not uncommon. I wanted to consider the dynamics of power as a provocation to reflect on who gets to write these histories and how are they represented (or not) in the archive.’ Reproduced in pink – referencing the pink cast of military-grade film, used in order to be able to identify targets – Vora subverts and reclaims the colour and context of the original image. During the process of making this work, Vora explains, she moved away from binary understandings of photography towards ‘how images can be used as a tool to contemplate histories – where can images lead you? Does it provoke you to unravel more of the narrative where answers don’t exist’.

‘I Dreamt of Lost Vocabularies’ articulates the often unspeakable aspects of diasporic heritage. As Vora explains: ‘I wanted to dream through this work regardless of how painful it is to think about the questions, conversation or parts of my history that have been overlooked, marginalised or forgotten – narratives that are all too often left outside of the frame. Each piece has its own title – somewhat poetic in approach but each carries a weight and burden of history.’

Vora describes the 20/20 residency as generative; it allowed her the opportunity to expand the collages, already sculptural in their approach, into three-dimensional pieces, too. Four new works reflect another part of this porous and capacious story. Crafted in metal and holographic film is a megaphone, ‘I Dreamt of Lost Vocabularies’. Pouring out of its centre is a textile form of twisted silk and rope, tongue-like, red, pink, orange and yellow: a call to arms, to protest, to project your voice. The sculpture ‘Brave the deluge. Not now. But now’, comprises a base made in the shape of an eye, covered in turn with the repeated image of an eye. This detail is taken from a Pathé film made at the time of the expulsion, a prophetic image of a local man with a crack in his glasses expressing his happiness that Uganda was to be returned to Ugandans. From this ocular base, an imitation of a Doric column rises proudly, a totem of western civilisation and power, embodied in ancient architecture but here made small, absurd and alone, redundantly holding up nothing. Another piece, ‘The scars of our past are especially sharp’, imagines a scene of tense waiting, reinventing the form of the photograph again, cut-out shapes arranged into a miniature stage set: a diorama of a family, their sepia suitcases stacked high behind them, their unknown fate ahead of them.

‘I Dreamt of Lost Vocabularies’ also includes mixed-media drawings, each presented as a structure to house a miniature object, a possession symbolic of crossing borders: a suitcase, a book. ‘The drawings are almost a facsimile of some of the visual material I have been navigating as residue and reference to the obfuscated narratives that are not as easily recalled or remembered’, Vora explains. Vora’s delicate drawings on paper depict images from her family archives from the 1980s and 1990s, with photo-transfers of newspaper images of the era, ‘tracing the trajectory of parallels of stories’. The circular shapes reappear as part of Vora’s language, a reminder of the dispersal of people, and her work’s mission to create a map, to join the dots.

When I look at these meticulously crafted pieces, time collapses, geographies are folded into a single place, bodies and landscapes that have never met in time or space riff off each other and intertwine. I have the impulse to reach out and trace the lines with my fingers, to open up these portals and step inside them. I am reminded of what Edward Said wrote in ‘Culture and Imperialism’ about resilience and resistance: ‘Survival in fact is about the connections between things.’ [2]

[1] Unless stated otherwise, all quotes are Bindi Vora in conversation with the author, May 2024.

[2] Edward Said, ‘Culture and Imperialism’, Vintage Books, London, 1993, p.407.